52 Essentials: No. 14, The Book of Genesis - Illustrated (2009) / Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus (2016)

Welcome to Maps & Legends, a project by two new parents looking forward to sharing our favorite art and culture with our new edition. Each week in this space, we'll pick a personal favorite of ours (or at least a favorite of one of us) and write about what it means to us and why we're excited to pass it down.

Max is days away from his first Passover and also his first Easter. It'll be a while before the two of us have to think seriously about how we--a couple of secular agnostic parents raised Catholic and half-Cath/half-Jewish, respectively--are going to educate our son on his various religious heritages. At the same time, though, we know that first impressions can count for a lot.

My own first impressions of the world growing up in St. Louis, "The Rome of the West", was that everyone was basically Catholic the whole world over. People might disagree here and there, for sure, when it comes to what we call ourselves, where we worship, what prayers we recite in what language. But all of that aside, we were also basically the same. We all had the same point of reference, didn't we? How many Bibles are there, after all?

You might call it the naive optimism of youth, but it was probably mostly the product of growing up in such a homogeneous environment. Living in a predominantly Catholic city, going to Catholic schools, hanging out with other Catholic kids. It can give you a pretty myopic view of the world. My Catholic education taught me that there was basically one correct way to view the world and all others were simply flawed in one respect or another. My Catholic upbringing taught me that the Bible had one definitive interpretation, despite the fact that it contained two mutually exclusive creation myths in Genesis, four distinct depictions of Jesus's life and ministry, and--as a general matter--sections that flat-out contradict other sections. It taught me that the Jewish Faith (for example) wasn't wrong, per se, it just failed to accept that the Old Testament was really a collection of preludes and allusions to the coming of Jesus, which was the culmination of all human existence.

In other words, growing up Catholic can make a person pretty insufferable. But then maybe that's true of any religious upbringing.

I don't expect that Max will have the same limited perspective that I did, growing up in Seattle instead of St. Louis. (Or maybe I should say that his perspective will be limited in new and different ways instead.) First off, his mother is half-Jewish on her father's side. So we put up our first Christmas tree with a Hanukiah next to it, and we'll be trading off hosting Seders with our Jewish friends in Seattle before we fly home to be with my side of the family for Easter.

Regardless of what traditions we pick and choose to incorporate into our family, though, the real trick will be introducing Max to the idea of conflicting interpretations. That is, the idea that the same story can say something entirely and radically different to different people. It's one thing to say that Matthew, Mark, Luke and John each had a different take on the same story. It's another thing entirely to say that the interpretation of a cartoon pornographer or a sex worker advocate can each be as valid as that of a priest or an apostle.

On our bookshelves, we have a row dedicated to religious topics leftover from my undergraduate degree in Religious Studies. There are copies of the Bible and other holy texts alongside essays on theology and the history of organized religion. Right above that is a shelf of comic books. Nestled between the two are a couple of comic book depictions of the New and Old Testaments by cult comic artists R. Crumb and Chester Brown (each available at Amazon). The former is (in)famous for the sexually explicit Fritz the Cat and counter-culture icon Mr. Natural. The latter rose to underground fame in the 1980s before diving into confessional autobiographies and gaining his own infamy for promoting the legalization of prostitution.

So naturally they both decided to release comic book interpretations of the Bible.

The two artists bring two very different sensibilities to their works. Crumb brings his typical "warts and all" realism, dotting every pour of his subjects' skin and leaving no human feature un-exaggerated. It's a style that can be aesthetically off-putting at best and accused of racist or anti-Semitic caricature at worst (and with very little imagination). The narrative approach is literal. Crumb declares in the first line of the Introduction that his mission was to "faithfully reproduce[] every word of the original text" (though, he cops to "ventur[ing] a little interpretation of [his] own" in "a few places").

Here's how he explains his motivation:

Every other comic book version of the Bible that I've seen contains passages of completely made-up narrative and dialogue, in an attempt to streamline and "modernize" the old scriptures, and still, these various comic book Bibles all claim to adhere to the belief that the Bible is "The Word of God", whereas I, ironically, do not believe the Bible is "The Word of God." I believe it is the words of men. It is, nonetheless a powerful text with layers of meaning that reach deep into our collective consciousness, our historical consciousness, if you will. It seems indeed to be an inspired work, but I believe its power derives from its having been a collective endeavor that evolved and condensed over many generations before reaching is final, fixed form as we know it...

Crumb's "warts and all" approach has the paradoxical effect of bringing out both the sacred and the profane dimensions of the Book of Genesis. Lines that sit fairly lifeless on the page, such as the creation of all existence tossed off in a few sentences at the beginning, assume their rightful grandeur and majesty.

On the other hand, the dry business of the endless geologies that were vital to establishing the proper heritage of the later Bible heroes (including Jesus himself) highlight the comparative insignificance of so many minor figures in the grand scheme of things.

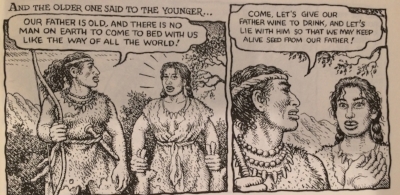

And, of course, there are the unsavory aspects of humanity's origin stories. The rape, incest and murder, as well as the temperamental divinity throwing tantrums over His inability to control his flock.

Crumb's literal approach was bound to attract criticism, if only by the appearance of his name--best associated as it is with anthropomorphized cat orgies, among other full frontal assaults on decency. Some have accused him of highlighting the prurient at the expense of the poetry, while others argue he misses the forest for the trees. One of the more interesting takes I've seen called him out not for being too literal but actually not literal enough:

To be truly faithful to the letter of the narrative – to be fully and deeply literal – such an adaptation would pursue three objectives. First, it would be unremitting in its attention to textual detail, reminding us of what even the best-known text actually says and shows. Second, it would be equally committed to “literally” rendering all that the text does not show, reminding us of what Genesis refuses or fails to depict. Third, it would make the reader aware of how the scripture’s isolated events, actions, and verses acquire their form and content in relation to one another and to a larger narrative whole.

What this critic is describing is the considerable labor involved in Biblical exegesis, which is not for the faint of heart or weak of mind. It's a very deep dive that requires an extensive familiarity with the historical time and place in which the texts were written, the attitudes at the culture and the realities of the world at that time. It is, to be certain, not the sort of exercise that lends itself to a singular, definitive, "universal" (or, as derived from Greek, "catholic") interpretation.

Which leads us to Chester Brown's stab at the same source material in the recently published comic essay, titled in full:

Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus - Prostitution and Religious Obedience in the Bible - A "Graphic Novel" Containing Adaptations of Certain Biblical Stories as Interpreted by Chester William David Brown and Published by Drawn & Quarterly Which is Located in Montreal

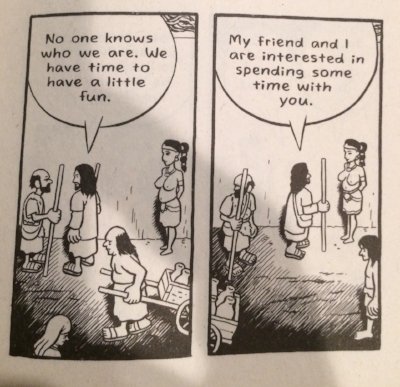

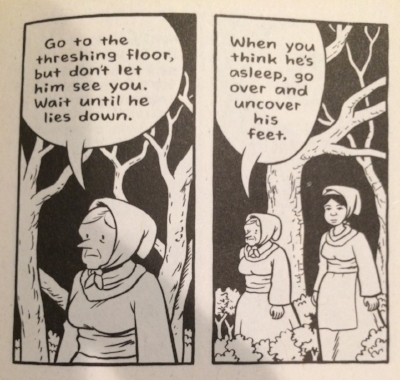

Needless to say, Brown took a different approach with his adaptation. His drawing style fits the mission of the book. The edges of his human characters are rounded of their rough edges, the pocks and blemishes are bleached out, and the sexual features are exaggerated not to emphasize the base humanity of the characters but their roles as prostitutes and patrons. Brown is less interested in illustrating the Bible than in using the Bible to illustrate a point.

The arguments he makes are bold to be sure, and sure to be rejected by many a believing Christian. Brown clearly understands that he's playing with fire, seeing as he dedicates nearly a quarter of his book to backing up his two-fold thesis: First, that the G_d of the Bible favors those who break the rules in pursuit of a full life over those who drudge through life blindly obeying them. Second, that in keeping with a lust for life, the Bible not only condones sex work, but the most venerated woman of the Old and New Testament, Jesus's mother Mary, was herself a prostitute.

Brown builds his argument with citations to Biblical scholars Jane Schaberg and John Domnic Crossan, explaining in fine detail where he agrees and disagrees with their work in reaching his own conclusions. He openly acknowledges whenever he strays from the literal text of the Bible, either by extrapolating his own content or correcting what he believes are the original writers' or translators' mistakes.

So for example, Brown re-frames the story of Cain and Abel as more than a simple clash between brothers, but as a dispute between blind piety as represented by Cain (who adheres to his father Adam's strict rules against animal husbandry) against vibrant defiance as represented by Abel (who realizes that sometimes you're better off when you break the rules). As we know, G_d showers blessings on Abel's offering but rejects Cain's, and Cain in his confusion and anger, murders his brother in cold blood before being cursed by G_d for the rest of his days.

A literal take on the story (as we saw in Crumb's version) provides no explanation for G_d's displeasure with Cain's sacrifice. leaving the Almighty seeming capricious and unpredictable. Brown's version fills in that gap in the narrative. According to Brown, G_d favored the brother who vigorously pursued a full life and punished the one who begrudgingly followed the rules. Cain's fury over G_d's slight is now far more understandable and also more relatable. What could be more unfair, more enraging, than getting punished for following the rules? And yet the Bible according to Brown teaches us that there's no reward for following the rules for its own sake, particularly when it comes at the expense of reaching our full potential.

Told through Brown's lens, the story of Cain and Abel parallels neatly with the parable of the Prodigal Son, which Brown similarly interprets as the vindication of the lascivious son, who gamble his life away yet lives a rich full life, over the blindly obedient son, who plays it safe only to become bitter a old man who rages against his father. (Again, that is, as the story is interpreted with a bit of creative license on Brown's part.)

Brown also recounts a series of stories from the Old Testament involving prostitutes (including characters explicitly identified as such in the Bible as well as others that Brown interprets to be prostitutes based on the context).

These stories form the backbone of Brown's central, more controversial argument--that the Virgin Mary herself was a prostitute, and that Jesus's teachings must be understood from the perspective of a man who did not shame his mother but instead saw G_d's salvation in transcending G_d's laws (just as his mother had).

It's a bold argument, but Brown shows his work. You can disagree, but it's on you to draw a better conclusion.

Growing up Catholic, going to Church every Sunday and attending Catholic school from kindergarten through high school prepared me for a lot of things. Wondering whether the Virgin Mary might've been a prostitute was not among them. Bible readings were simple back then. The message was always the same, give or take a homily. Simple, straightforward, and very, very dull. The challenge for me as a young alter boy was less about understanding why G_d would favor Cain's offering over Abel's than about staying awake when Father told you for the umpteenth time to love your neighbor because something something reasons.

The creation of the universe, the fall of humanity, the flood, the Exodus, the rise and fall of kingdoms, the birth of the Christ, his resurrection and the End Times ... the entire history of humanity (from a certain point of view) has been rendered flat, inert and incredibly boring by centuries of Papal doctrine.

If there's real value in these texts, though, that make them worth revisiting after two thousand years or more, it should come to life when you engage with them. They should still be able to surprise you, to challenge you, to titillate, confuse or enrage you, possibly all at once. After all, the divine can be many things to many people, but what good is a boring Almighty? And what's more boring than agreeing with everyone all of the time?